A COUPLE of days ago, we stood gazing up at the star-filled evening sky. It was the first really chilly evening of this autumn.

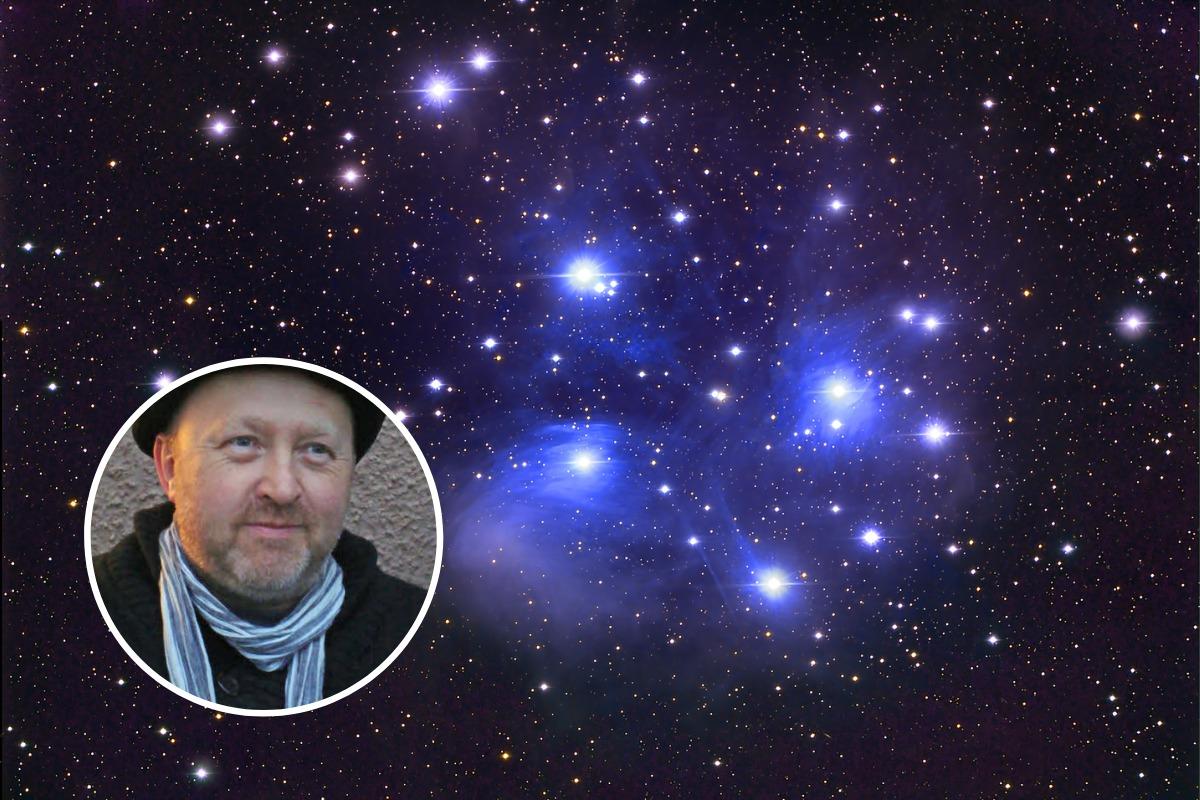

The moon was still low and I searched the sky for a cluster of stars I’ve always called the “seven sisters”, but which are more commonly known as the Pleiades. These stars have a particular significance at this time of year, as it's when they are at their highest in the night sky.

After I’d pointed them out, my youngest daughter asked a good question: “Dad, why is the darkness darker than usual, but all the stars brighter than before as well?”

It was true, the night sky did seem much darker, and the stars were making the most of it. They were spectacular and we stood stargazing like mesmerised rabbits. It’s such a primeval feeling, looking up at the stars in wonder, trying to make sense of what you see.

As we stargazed, I explained that the sky is dryer and so less humid at this time of year, making visibility better. As a result, the night sky is more vivid, which makes the stars seem to shine brighter to our naked eye. There are other reasons, I explained, such as the tilt of the earth in wintertime and that it gets darker earlier and for longer.

But as I tried to impress with my limited astronomical knowledge, my son suddenly came out with an explanation that was a simpler but no less true: “I think the sky is darker, and the stars are brighter, because it’s a sign Hallowe'en is approaching. Basically, it’s a Hallowe'en sky.”

I think he was talking about the atmosphere of the evening, with the chilly crisp air and clear starlit sky making him think about guising. But he was right, as Hallowe'en originates from an earlier Celtic event called Samhain (pronounced sow-in, pronounced as in the word for pig).

Samhain marked the beginning of the dark time of year and it was when Pleiades reached its zenith, when its stars shone brightest in the sky, that Samhain was celebrated. So, there is real truth to say it’s a “Hallowe'en night sky”. It doesn’t correspond exactly, as it's early November that the Pleiades shine brightest, but dates are different since the change from the old Julian calendar. But that’s a small detail. The fact is our ancestors used the stars to mark the year and the changing seasons, and the Pleiades was an important part of that and determined when Samhain took place.

“But I can only see six bright stars there, dad,” my ever-observant daughter commented. Cue a story!

The bright stars of the Pleiades seem to have been noticed by many early people and it was one of the first star clusters to be named. The term Pleiades is Greek and usually said to translate as sail. Greek mythology explains how the stars were placed in the sky.

The myth tells us the “seven sisters” were originally the daughters of the Titan god Atlas and the nymph Pleione. Atlas was the god condemned to hold up the sky for eternity. As a result, he couldn’t protect his daughters when they were being harassed by the great huntsman Orion, who pursued all seven sisters with unwanted amorous advances.

But Zeus, the sky god and king of the Olympian gods, heard the sisters’ cries for help. I think he should have punished or restrained Orion, but I’m not a god, so what do I know? Instead, Zeus’s solution was to turn the seven sisters into doves.

To escape from Orion, they flew into the sky and became the bright stars known as the Pleiades, or the seven sisters.

Even after this, Orion’s desire for them wasn’t vanquished. He pursues them still, as he can be seen as a constellation of stars in the winter’s night sky, chasing the poor maidens in the heavens.

As I told the story, we studied the sky and tried to see the images in the stars which inspired the mythology. We joined the stars in a dot-to-dot game with our imagination.

“But I still only see six sisters,” protested my daughter.

“Ah, there’s a reason for that,” I explained.

She waited as I assembled my recollections of the myth.

“According to the myth, one of the sisters left the sky out of shame, because all the other sisters married gods and she married a lowly human instead. That’s why you can now only see six.”

My daughter raised an eyebrow: “Maybe marrying a god isn’t as good as it’s made out to be anyway, if you end up hanging about in the sky all the time. Maybe the missing sister is having more fun, it must’ve been true love.”

“Maybe,” I replied.

Storytime was over and we went back inside as it was cold.

What I didn’t explain to them is that this story may be a version of the oldest-known story in the world. There are so many similar stories about the same stars from many different cultures, which also have seven sisters, or sometimes brothers, then one leaves. There’s even a version from Aboriginal tradition in Australia.

This seems to suggest the original story comes from a time when the seventh star was visible. It’s actually still there, but now too dim to see with the naked eye. It faded from human vision around 100,000 years ago, a time when all humans lived in Africa.

And so, very possibly, the original story of the seven sisters, with one leaving, comes from an ancient tale made by our African ancestors over 100,000 years ago, from a time when people remembered there used to be seven stars.

“Can we do that again?” my daughter asked as we settled into our house. “You know, tell stories about the stars?”

“Sure,” I said, thinking I’d better get a book. And so I did: Treasury of Folklore: Stars and Skies: Sun Gods, Storm Witches and Soaring Steeds.

Great book and I’m now ready for our next evening storytelling under a cold, crisp, clear winter sky.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here