ST ANDREW’S Day is almost upon us, and in East Lothian we can claim a particular connection to it. As soon as you enter the county, there are signs which declare proudly that East Lothian is “the birthplace of the Scottish Flag”, with the date 832AD. This, of course, refers to the Battle of Athelstaneford, which was fought between a combined force of Scots and Picts against a much larger army of Saxons.

I have given an account of the tale in this column before, but the best telling of it for me was by the wonderful storyteller Angie Townsend, who personified the mix of a passion for history and a love and talent for storytelling. Angie is missed and remembered by so many people.

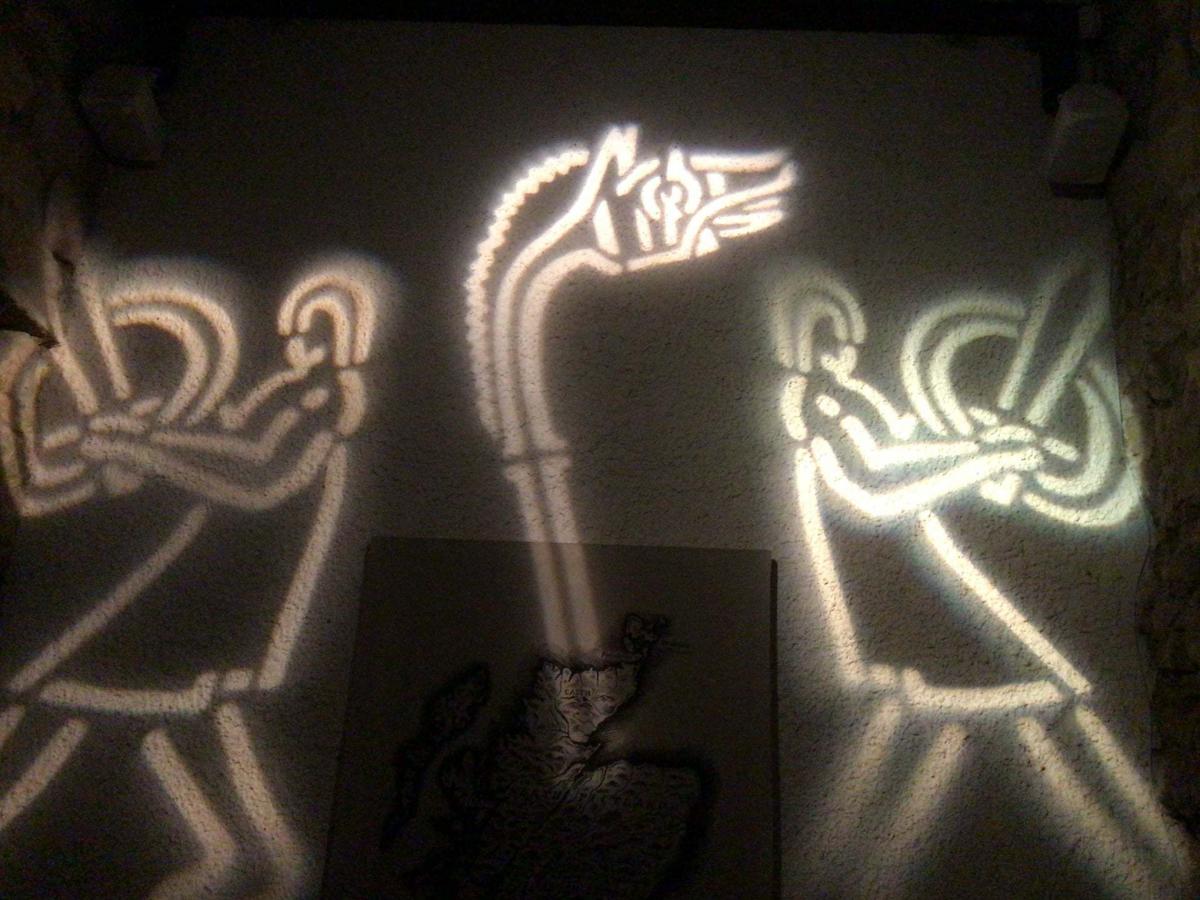

It is a historical tale which is part of Scottish history itself. I will not retell the full story here again, as I could not do justice to the wonderful telling of the story which can be experienced at the Flag Heritage Centre at Athelstaneford, found in the old doo’cot behind the village kirk. The doo’cot is an interesting old building in its own right, but venture inside and you will discover that the Scottish Flag Trust have created a fantastic audio-visual experience telling the story of the battle. The centre is currently closed for the winter, but it will be open for St Andrew’s Day on Monday.

The importance of the story for St Andrew’s Day is the connection it makes between the battle and St Andrew, and Scotland’s national flag, the Saltire. It tells us that the battle was fought between a force of Scots and Picts led by Hungus or Angus, and a force of Saxons or Northumbrians whose leader was called Athelstan.

St Andrew visited Hungus in a dream before the battle and told him that victory would be won. When the battle itself was raging, a miraculous vision of the St Andrew’s Cross was seen shining in the sky, giving a boost to the morale and fighting spirit of his warriors. The result was a victory over the Saxons, and the death of Athelstan. Thus, after this victory, according to the tradition, the Saltire or St Andrew’s Cross became the flag of Scotland, and St Andrew the national patron saint.

While there is no written reference to the battle in Scotland from the period it was said to have taken place, this is not surprising, as it was a time for which we have little or no documentation for anything. The earliest written mention of the Battle of Athelstaneford in Scottish history comes from the early 15th century, 600 years later. This account is in a document called the Scotichronicon, written by Walter Bower.

He was born in Haddington in 1385, studied and graduated from the University of St Andrews and became the abbot of the monastic community at Inchcolm Abbey. It was in his later life, when abbot, that he wrote his chronicle. This document has been described by some Scottish historians as a valuable source of historical information, especially for the times that were recent to him or within his own memory. But he also wrote about earlier times, and this included the battle at Athelstaneford.

Bower’s account includes the scene where Hungus is visited by St Andrew in a dream before the battle. He was told that the cross of Christ would be carried before him by an angel.

There was no mention of a St Andrew’s Cross in the sky in this version. It was in later accounts, from the 16th centuries onwards, that we have the description of an image of St Andrew’s Cross shining in the sky.

So the story of the battle we know today comes from different historical sources which have been weaved together. This is nothing unusual in history, since different sources often have different details.

Bower was writing in the early 1400s. The bitter and bloody struggle to retain Scotland’s independence was not just a recent memory but also a current reality for him. Parts of Scotland were still occupied by England, and Bower had been involved in raising the money to release Scotland’s king, James I, from English captivity.

Also, Scotland’s early historical records and documents had been deliberately destroyed during the invasion by the English king Edward I. This was done in part as an attempt to remove historical evidence that Scotland had been an independent kingdom. The idea was simple: take away a nation’s history and you strip it of its identity and justification for its independent existence. The theft of the Stone of Destiny was part of this process (I will leave the issue of whether it was really taken, as that’s another story!).

Part of Bower’s motivation in writing his Scotichronicon was to help restore this stolen history. He was a scholar and a man of the church. In his time, the figure of St Andrew had become a prominent presence in Scottish society.

The greatest church building in the land during his time was the Cathedral of St Andrew, which housed relics of St Andrew himself. It had taken over a hundred years to build and wasn’t formally consecrated until 1318, just four years after Bannockburn. The ceremony of course included Robert the Bruce and at it thanks was given to St Andrew for Scotland’s victory.

Less than 100 years after this, in 1413, the University of St Andrews was established and Walter Bower was one of its first students. By this time, the Cathedral of St Andrew was a place of pilgrimage, with thousands travelling there to venerate the saint’s relics. A pilgrimage route from the south took in the shrine of Our Lady at Whitekirk, not far from the site of the battle, and many pilgrims took a ferry across the Firth from North Berwick, where the ruins and remains of the old St Andrew’s Kirk can still be seen close to the Scottish Seabird Centre.

So as he sat down to write his history of earlier times, he was able to trace this connection to St Andrew, using the limited earlier written accounts, such as those of John Fordun, who lived in the 1300s. While Fordun doesn’t specifically mention the location of Athelstaneford, he records a battle which took place between the Picts led by Hungus and a force from the south led by Athelstan, and said the location of the battle was about two miles from Haddington. The account of St Andrew appearing in a dream to Hungus is also described by Fordun.

This creates a powerful link to the development of the written version of the story. Let’s remember Bower came from what is now East Lothian. Let us also remember that people in the early centuries stored and passed on much of their historical knowledge not in the written word but in memory and handed down oral traditions. People told stories, remembered them and told them to the next generation. Undeniably, some details would be forgotten or changed over time, but the bones of the story would be handed down. And that would include reference to locations of significant events in the local landscape.

Bower will have had access to this rich oral tradition of local stories based on handed-down collective memories of past events, which is perhaps why he was able to name the location. The later writers who added to the story of the battle will likewise have found new sources in the oral tradition to add to the narrative. Even in the 19th century, cartographers mapping the area were able to identify locations traditionally associated with the battle from local people who were custodians of ancestral memory.

This is how the story of the Battle of Athelstaneford and its connection with St Andrew and the Saltire has evolved.

Books have been written, and will continually be written, discussing the details and sources of the battle, but what is not in doubt is the historical and national importance of this great story; it is a narrative told by the voices of thousands of Scots, and now wonderfully retold by the Scottish Flag Trust in their Flag Heritage Centre at Athelstaneford, which atmospherically overlooks the sites of the battle.

Happy St Andrew’s Day to everyone.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here