IN THE 18th and 19th centuries, many of East Lothian’s landed estates were divided into a number of farms, each with their own steading.

Steadings were used to house animals, store equipment and crops, and often contained industrial buildings such as engine-houses and mills.

Nearly all the farm steadings had large brick chimneys for steam engines, which provided power for threshing, often replacing horse mills.

Cattle were traditionally kept in cattle-courts during winter – hence the large size and often symmetrical design of steadings.

Cart and granary sheds were built with an arcaded ground floor, while a small windowed upper storey functioned as a granary. Often, this was the only two-storey building in a steading.

READ MORE: Down Memory Lane: Diving into East Lothian's pools of yesteryear

Likewise, the horse mill was often noticeable because of its octagonal roof.

In several steadings, a doo’cot was often incorporated to provide doves for fresh meat in the winter.

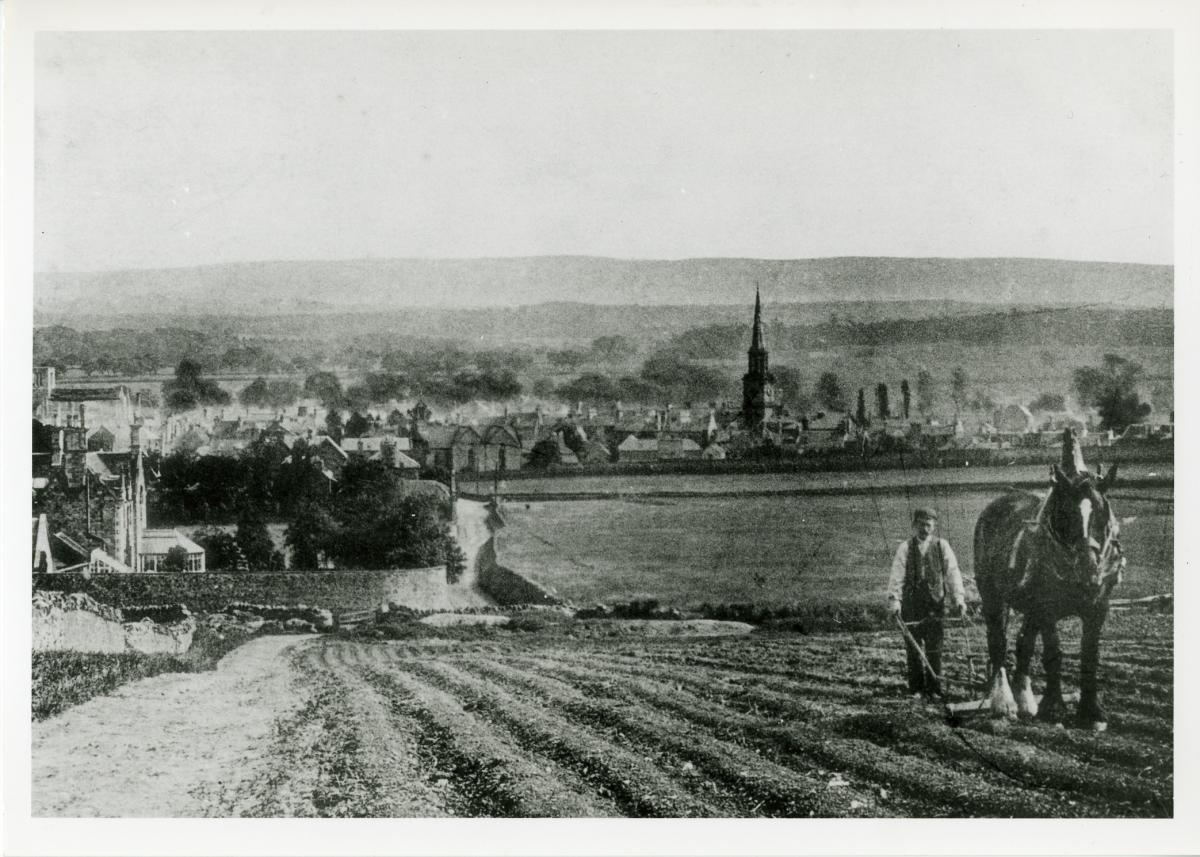

Over time, established practices and traditional farming methods gradually disappeared, and farms with delineated fields and a central steading unified their work buildings, stores, cattle courts and housing for farm workers.

Most steadings have now been converted into housing, as farms have been consolidated into larger units.

Many people researching their Scottish ancestry are likely to find a relative who was a farm servant or agricultural labourer.

Prior to the industrial revolution and availability of work in towns, a substantial percentage of the population lived and worked in the countryside.

People lived in small settlements of up to 20 households, growing their food on surrounding strips of common land.

READ MORE: Down Memory Lane: Looking back at schooldays of yester year

The 18th century was, in Scottish agriculture and elsewhere, regarded as the great ‘age of improvement’, then, during the industrial revolution, particularly from the 1820s onwards, the population increased rapidly and it was necessary to boost the amount of food grown. As farms grew in size, more people were needed to work them.

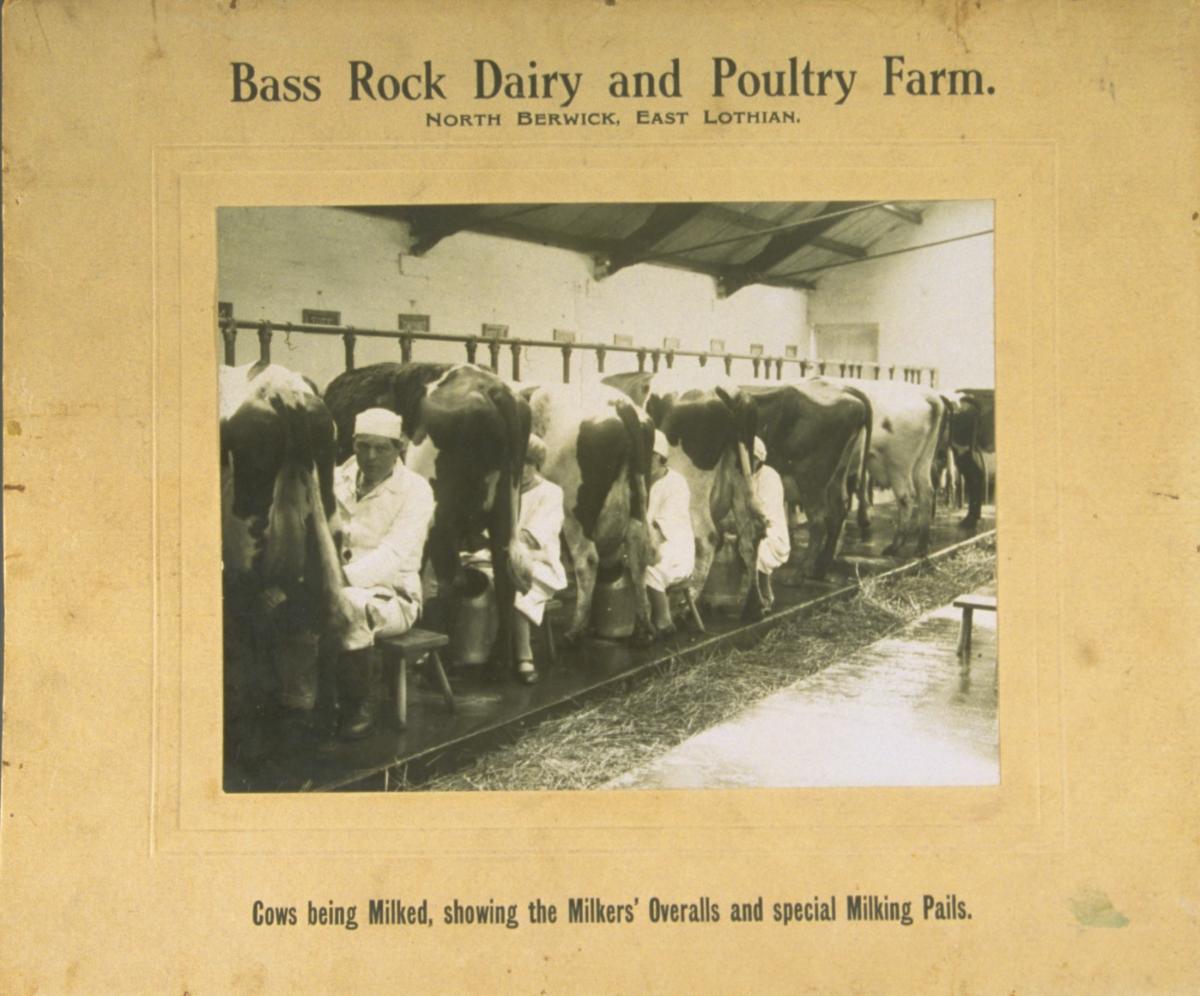

Farmworkers might include the grieve or foreman, bailies to look after cattle, ploughmen, dairy maids, housemaids, kitchen maids, ‘oot’ women, labourers, a handyman, and sometimes even the soutar (shoemaker), who probably worked for a local shop and visited the farms to repair shoes.

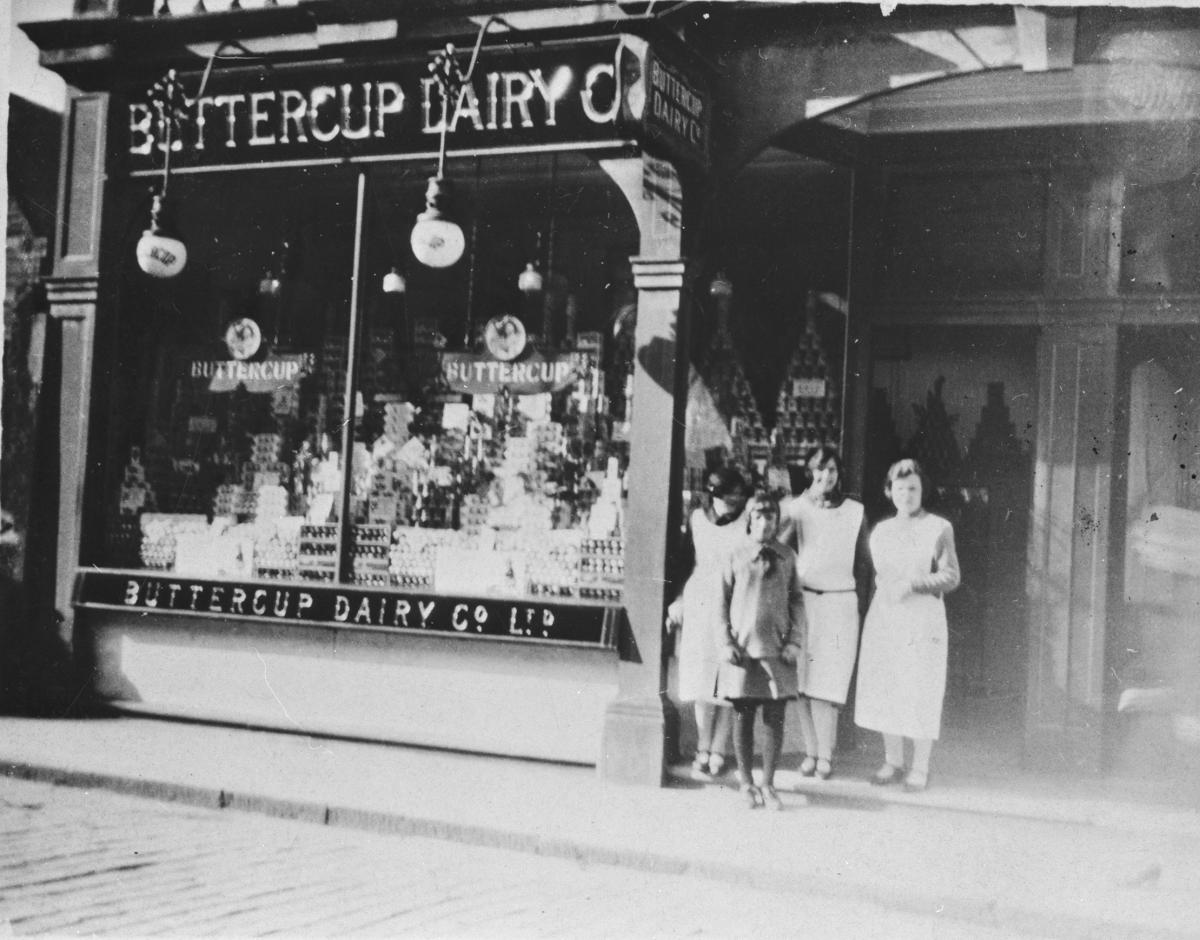

Some towns might also have a dedicated smithy/smiddy, or the blacksmith might have his premises in an ideal location to serve a number of farms.

The blacksmith shod the horses and made, repaired and sharpened ploughs, harnesses, and other tools.

At harvest times, hundreds more were employed on a temporary basis for berry picking or ‘tattie howking’ (lifting potatoes).

Children were also involved in farm work almost as soon as they could walk. In a very short space of time, they moved from feeding hens and bringing food to farmworkers to becoming involved in the arduous task of ploughing the fields.

READ MORE: Down Memory Lane: A trip back in time to East Lothian's cinemas

Farmworkers were rarely employed permanently and often lived quite a nomadic life.

They were usually hired on a temporary basis at a feeing market or a hiring fair, usually held every six months, in May and November. On accepting the fee, the farm servant would be bound to the farmer for the next six months to a year.

In many cases, the farm servant would not see much of his fee in cash but would be provided with a roof over his head and some basic food and fuel.

If he was a married man, he might be lucky enough to be taken on by one of the larger farms that provided accommodation for his family.

Otherwise, he would have to stay in the bothy with the single men while his family stayed elsewhere.

Sometimes there were cases in which the family of a farm worker were living apart from him in abject poverty and relying on the parish for assistance.

With the passing of time, mechanisation increased. Farms began to use equipment that could sow and pick far quicker than labourers. People also began to prefer non-agricultural jobs which were better paid, more permanent and had fewer of the challenges that came with working in the fields in all weathers.

l Article courtesy of East Lothian Council Archives & Museums. See www.johngraycentre.org

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here