A Musselburgh resident has paid tribute to the hundreds of prisoners of war, including several from East Lothian, who perished in the sinking of the Lisbon Maru – an armed Japanese freighter – during the Second World War.

Dr Iain Gow’s father Private James Gow, from Dundee, who served with the Royal Scots, survived the horror incident and went on to become a POW in Kobe Camp, forced to work in the docks.

A number of servicemen from East Lothian also survived the sinking and, like him, were interned in POW camps, some dying there.

On repatriation, Pte Gow remained in the regiment and was back in the fray at the end of the war.

Dr Gow, of Eskview Road, joined more than 100 former members of The Royal Scots (The Royal Regiment), traditionally the regiment for Edinburgh & the Lothians, their families, relatives and friends for the unveiling of two memorials at the National Memorial Arboretum in Staffordshire.

Also present at the event were several hundred other representatives from the Royal Navy, other regiments and corps.

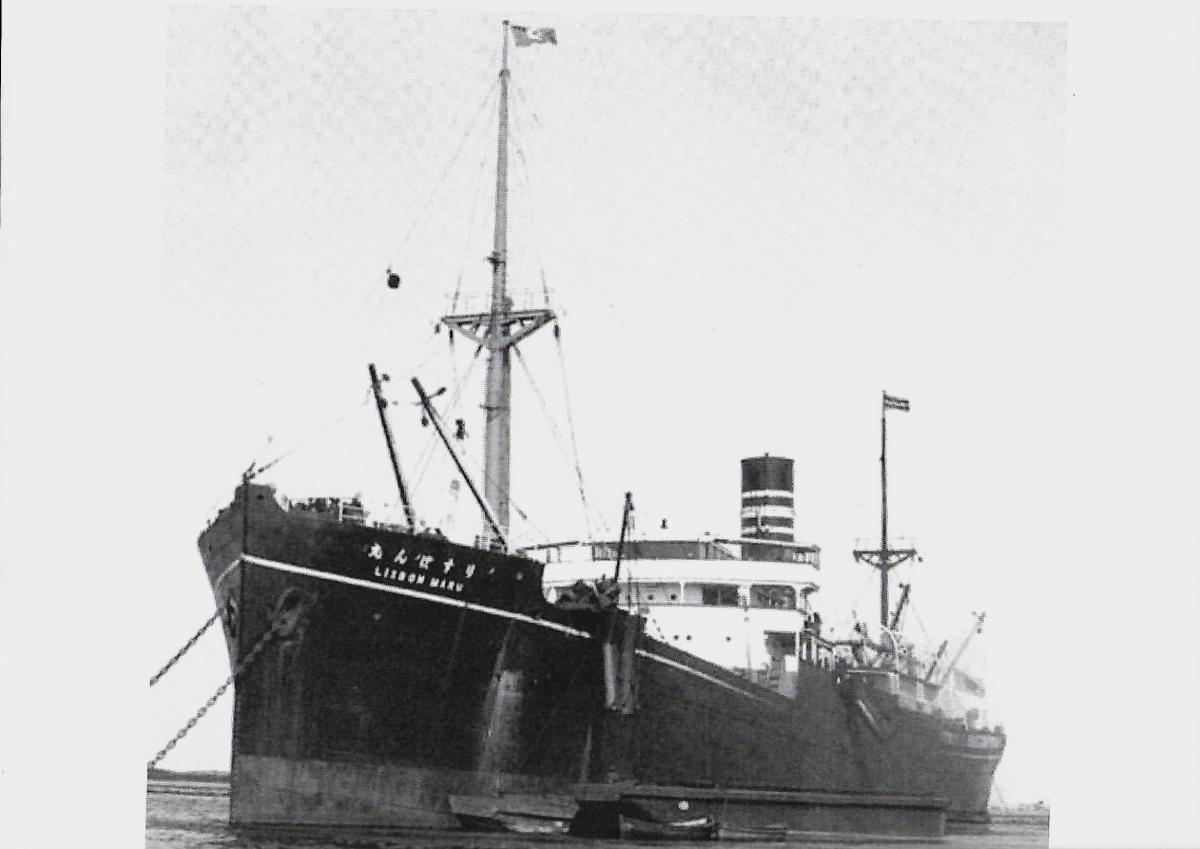

One memorial is dedicated to the 828 POWs who died in the sinking of the Lisbon Maru 79 years ago, when it was torpedoed by the submarine USS Grouper on October 1, 1942, six miles from the Sing Pang Islands in the Chusan (now Zhousan) Archipelago, off the coast of Chekiang Province, south of Shanghai.

She carried, in addition to 1,816 British POWs, 778 Japanese troops and a guard of 25 for the POWs, en route from Hong Kong to Japan.

An account on the Royal Scots’ website said: “The engines stopped, the lights went out and those few POWs who were on deck were pushed back into the holds. The ship’s gun began firing. The POWs were kept in the partially closed holds throughout the day with no food, water or access to latrines. No blame has ever been, nor ever must be, attached to the USS Grouper. There was nothing that identified her as carrying POWs; there were a large number of Japanese troops on board; and she was armed. Everything that could be seen identified the Lisbon Maru as a legitimate target.”

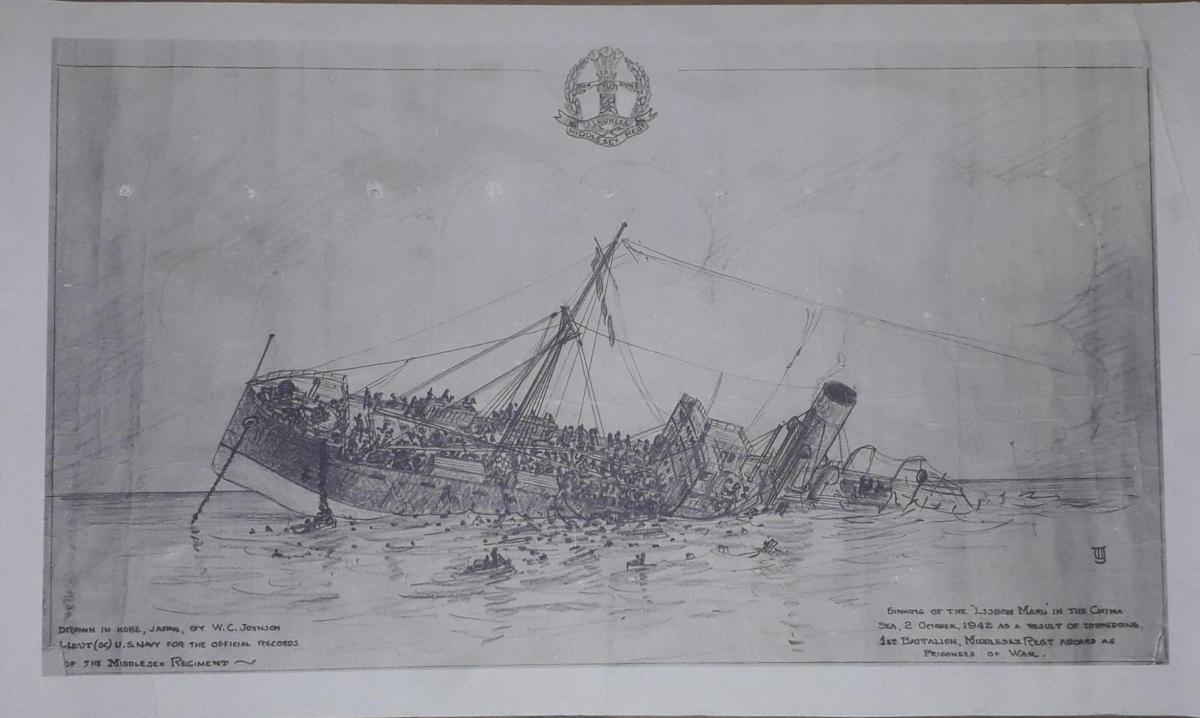

The Japanese troops were evacuated from the ship but the POWs were not and the order was given by the guard commander to fully close the hatches and batten them down with canvas.

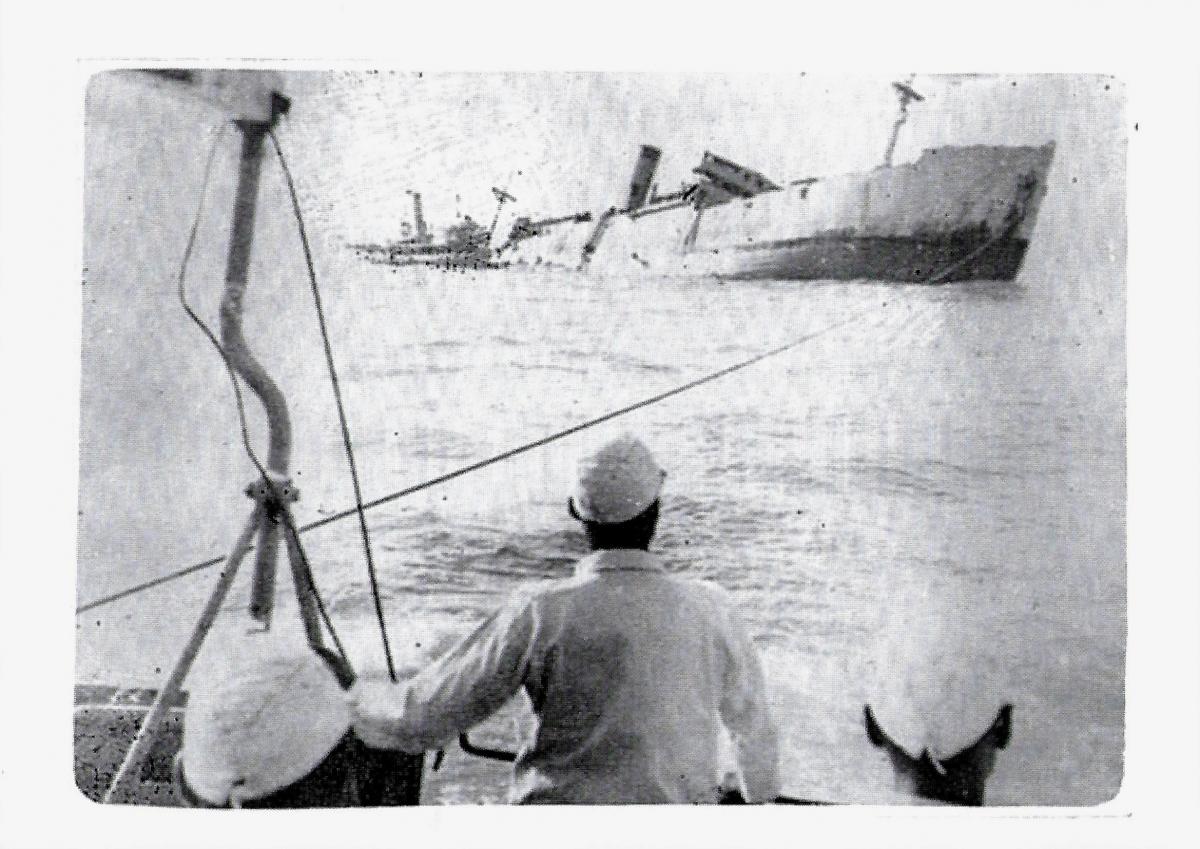

According to the account, by dawn on October 2 it was apparent that the ship was in imminent danger of sinking and the POWs broke through the battened hatches, plunged overboard and began swimming towards an island.

The remaining guards began firing at them until the weight of numbers of POWs pouring onto the deck overpowered them.

Between the ship and the islands were a number of Japanese auxiliary vessels and tugs, some of them surrounded by men in the water vainly asking to be picked up. If they were, they were then pushed back into the water; and the firing of shots could be heard.

The Lisbon Maru finally sank at about 10.45. At some stage, the Japanese boats started to pick up those prisoners still alive in the water and who had not drifted past them towards the islands.

The Chinese set off in junks and sampans to assist the survivors. They picked up a considerable number of exhausted swimmers, while other villagers assisted those who had drifted or swum to the islands and helped them to land on the rocky shores.

Some 200 survivors were assembled on the islands, where the villagers fed and clothed them from their own scant supplies and treated them with great kindness, until the Japanese landed in force on the following days and rounded up all but three of the prisoners. These three, all civilians who had been working in Hong Kong – two with the Royal Navy – were hidden by the village representative, who later arranged for their escape to Chungking.

Included amongst the POWs on board were 373 members of the 2nd Battalion The Royal Scots, who had become POWs upon the surrender of Hong Kong on Christmas Day 1941.

Of this number, 181 men (48.5 per cent) died, killed by their guards or drowned as a result of the ship’s sinking. Many more died as POWs from their treatment, working subsequently as forced labourers in Japan in support of the Japanese war effort.

Dr Gow, who is originally from Annan, lectured at Queen Margaret University in Musselburgh for 10 years. A reader in physiology and pharmacology, he taught science students and allied health professionals.

He is very much involved in the history of the Lisbon Maru POWs and he retains contacts in Hong Kong. He recently obtained some artefacts collected from the battlefield in Hong Kong, which he donated to The Royal Scots Museum.

He said: “When we were growing up, like most Far East POWs, dad never really talked about his experiences. We knew vaguely he’d been in Hong Kong, on the Lisbon Maru, and Kobe, but not the extent of the horror he’d experienced or witnessed. It never cast a shadow over our childhood. Christmas was always quiet; he preferred to celebrate Hogmanay and New Year for reasons which are now obvious to us.”

The other memorial – a five-ton block of Aberdeenshire granite – is sited close to the Armed Forces Memorial at the centre of the arboretum. It bears a bronze plaque inscribed with the badges of the regiment and the words: “In Memory of all those who served their Sovereign and Country in The Royal Scots (The Royal Regiment), 1st Regiment of Foot and Right of the Line, 1633-2006.”

The stone supplements the main Regimental Monument sited below The Mound in West Princes Street Gardens, Edinburgh, which was dedicated in 1953 and updated in 2008. The choice of the National Memorial Arboretum for this additional memorial was to commemorate all former members of the regiment, wherever they came from, including many from overseas, and highlight the regiment’s service as the British Army’s senior and oldest infantry regiment before it was merged into the Royal Regiment of Scotland in 2006.

Brigadier George Lowder said: “After two years of planning and preparation by a wide range of Royal Scots volunteers, it is great to see this project come to fruition, providing a suitable Royal Scot rallying point at the National Memorial Arboretum, Staffordshire, particularly for the many Royal Scots who live south of the Border. It is a fitting memorial to all Royal Scots and especially poignant to be unveiled on the same day as the Lisbon Maru memorial.”

Casualties of the sinking from East Lothian included: Pte Robert Archibald, Melbourne Place, North Berwick; Pte Joseph Bryant, Ormiston Crescent, Tranent; Lance Corporal James Cook, Ormiston Crescent, Tranent; Pte Thomas Marshall, High Street, Cockenzie; Lance Corporal John Ormiston, St Germain Terrace, Macmerry; Corporal Adam Peffers, Edinburgh Road, West Barns.

Survivors of the sinking (though some subsequently died as POWs) include: Lance Corporal David Black, Amisfield Road, Haddington; Pte Robert Clelland, Shaw Road, Prestonpans; Pte Robert Edgar, Dolphingstone Level Crossing, Tranent, who died in 1943 in the POW camp Kobe House; Pte Harold Golighty, Station Road, Haddington; Pte Harvie or Robert Harvey, Gardiners Road, Prestonpans; Pte John Mowatt, Lammermuir Crescent, Dunbar; Colour Sergeant Alexander Taylor, from Haddington, who died in 1943 in POW camp Hiroshima.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here