Dunbar author Dr Jan Bondeson continues his colourful exploration of the county’s rich past with a delve into the history of Spott

“OUT, damned spot! Out, I say!” – from ‘Macbeth’, by Shakespeare

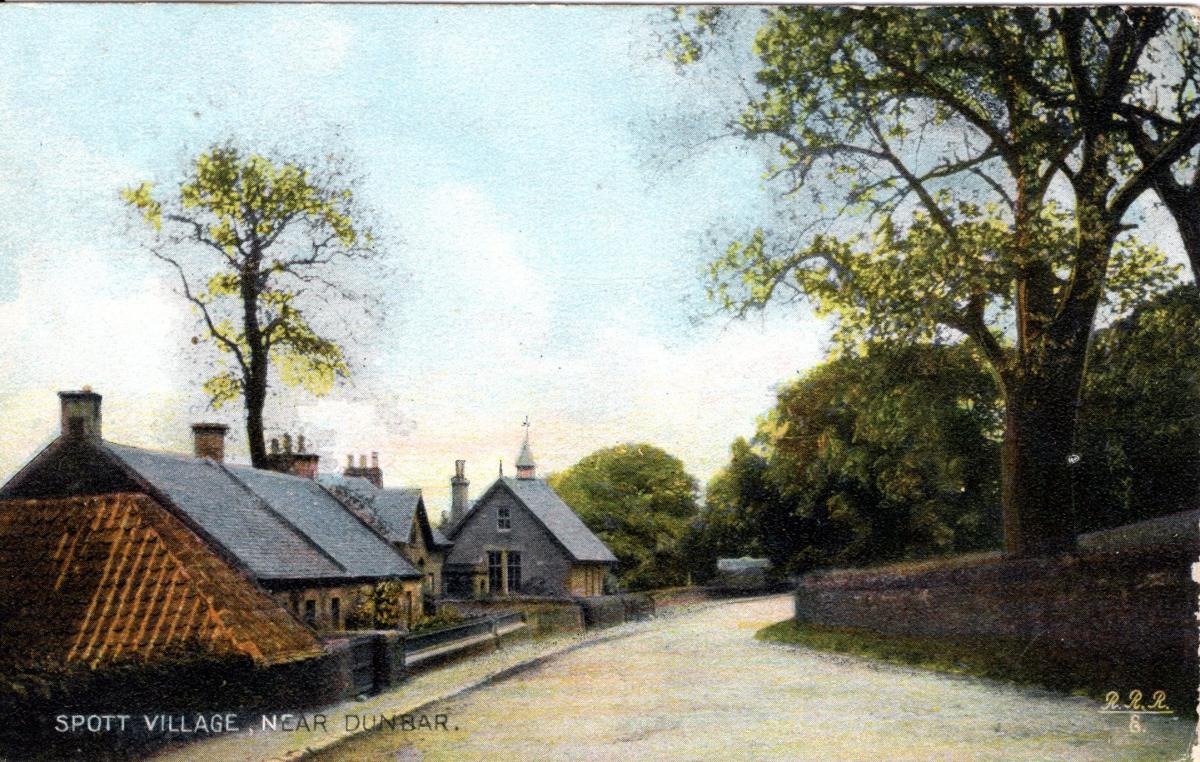

AS WE KNOW, Spott is a quiet East Lothian village, situated about two miles south-west of the bustling metropolis of Dunbar.

It has respectable antecedents from the Roman occupation of southern Scotland, with many ancient artefacts found by archaeologists.

Spott has a dark history in the annals of Scottish witch hunts, with many witches burnt at the top of Spott Loan as late as 1705.

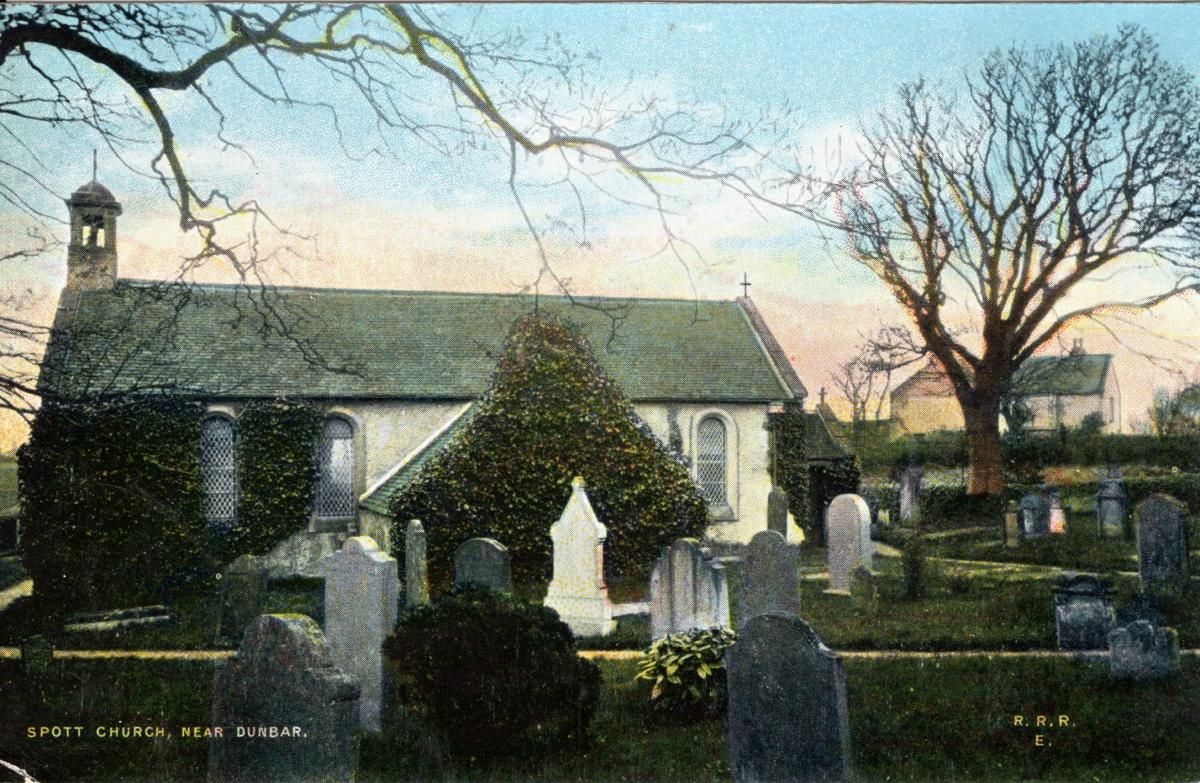

There was a church in Spott before the Reformation and it still stands today, although much repaired and altered in 1790, and later in Victorian times.

Stately Spott House has been the head of a mighty estate for many years, first owned by the Sprot family and later by Sir James Hope, before being purchased by a Dane in 2000 and later broken up into smaller lots of land and buildings.

The main road through Spott. A postcard by the celebrated North Berwick artist Reginald Phillimore

In the 16th century, Spott had bad luck with the parsons serving in its nondescript little church.

Robert Galbraith, parson of Spott, was murdered in 1543 by one John Carkettle, a burgess of Edinburgh.

His successor John Hamilton advanced to become an archbishop in the time of Queen Mary, but he dabbled in politics, was taken prisoner at the capture of Dumbarton Castle in 1571, and hanged in Stirling for his complicity in the assassination of the Regent Moray.

He was succeeded by the Rev John Kello, the first Reformed Kirk minister of Spott, who had been active as a parson at least since 1560.

He was a man of humble origins but considerable theological learning, of high moral values, and a fine preacher. Kello had married Margaret Thomson, a woman of the people, and they had three children named Bartilmo, Barbara and Bessie.

They all settled down at the manse and lived reasonably happily for a while, but the Rev Mr Kello felt ashamed of his wife and grew to hate her, hoping to better himself by marrying the daughter of the laird.

He tried to make money by speculating in property, initially with some success, but his affairs grew complicated, which added to his frustrations.

On Sunday, September 24, 1570, the Rev Mr Kello went into his wife’s chamber at the manse, as she was kneeling in prayer.

He seized hold of her with a hearty goodwill and strangled her to death with a towel, before suspending the body from a hook in the ceiling to make it seem she had hanged herself.

He cunningly left the key on the inside when he locked the front door of the manse, and went out by the back.

At the kirk, he delivered a more than usually eloquent sermon, before inviting some neighbours back to the manse to cheer up his wife, who had long seemed depressed and unwell, he said.

He feigned surprise at finding the front door locked from the inside.

He made use of another entrance, leaving the neighbours outside, as he said he would go and fetch his ailing wife.

Next, the Rev Mr Kello appeared at the window, calling out: “My wife, my wife, my beloved wife is gone!”

This account shows us that the Rev Mr Kello was a cool customer, able to persuade the neighbours that his wife had destroyed herself.

He might well have been able to remarry and live at Spott manse in comfort and security, happily ever after.

But his colleague the Rev Andrew Simpson, the first minister of Dunbar after the Reformation, had heard bruits that all was not natural about the death of Margaret Kello.

He confronted her husband, who lost his determination and confessed to murdering her.

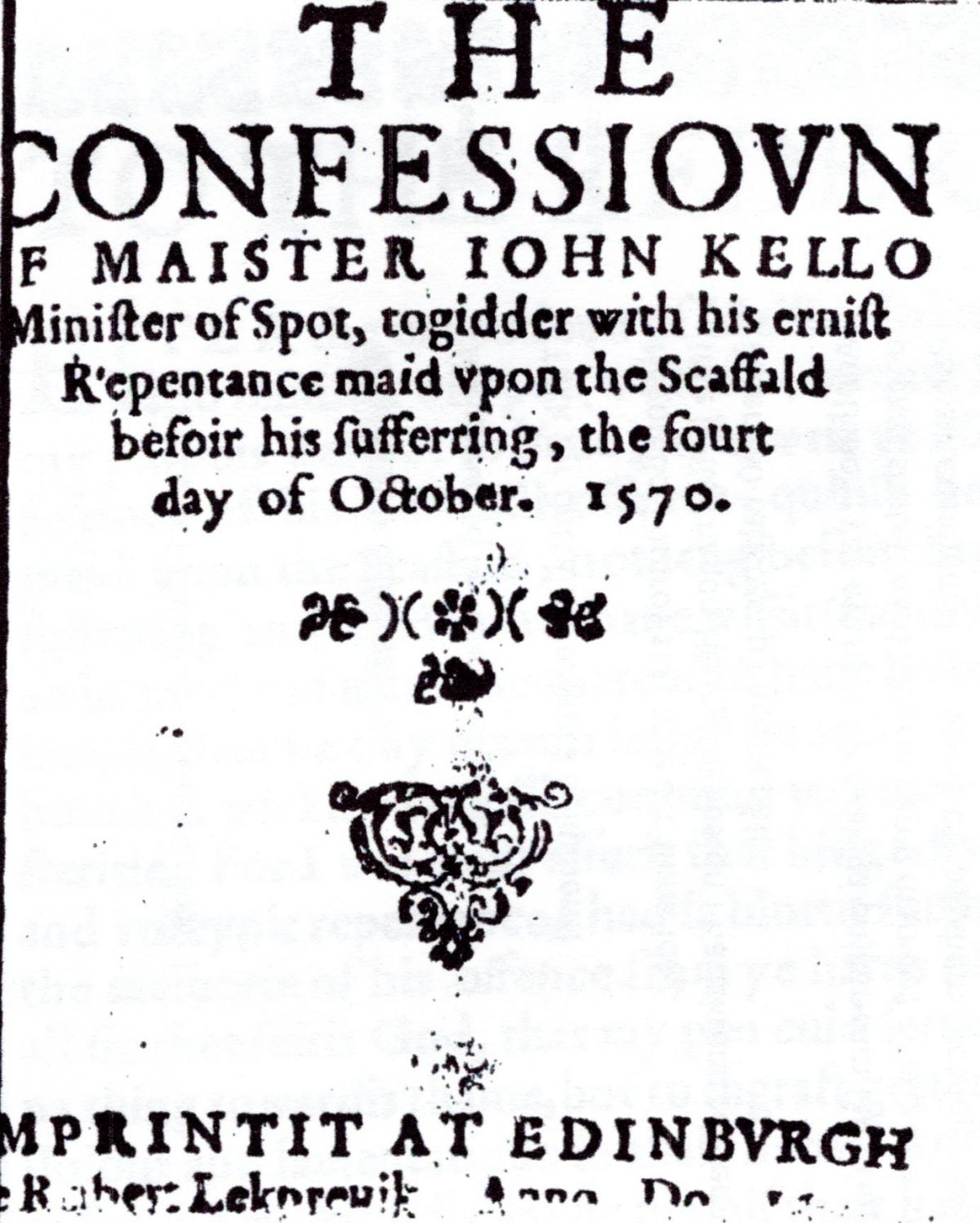

The Rev Mr Kello was taken to prison in Edinburgh, stood trial and was found guilty of murder, and was hanged on October 4, 1570.

A rare ‘Confessioun of Maister Iohn Kello, Minister of Spot’ (pictured below), probably ‘ghosted’ by some enterprising cleric, was printed by Robert Lekprewik in Edinburgh shortly after the execution, blaming Satan for corrupting the Spott parson’s mind.

Of the Rev Mr Kello’s three children, we hear nothing more of the two girls, but his son Bartilmo also became a parson, studying theology at the University of St Andrews, just as his father once had, and marrying the distinguished artist and penwoman Esther Inglis in 1596.

Bartilmo and Esther later moved south to England, where they had several children.

In pondering the case of the wicked parson Kello, it is notable that such a cool and crafty miscreant, who had successfully accomplished his purpose and avoided detection, would confess to the Dunbar parson in such a craven manner.

We do not know, however, how much local suspicion there was against the uxoricidal parson, and what evidence the Rev Mr Simpson had accumulated before he confronted his Spott colleague.

He remains unique in the annals of the clergy in preaching a fiery sermon in the kirk just after murdering his wife.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here