By Tim Porteus

GLENCOE is perhaps one of the most iconic places in Scotland, both in terms of landscape and history. The awe-inspiring mountains called The Three Sisters never fail to overpower the senses, while the glen itself is steeped in clan legends, tales and a fascinating, and at times brutal, history.

The journey to reach Glencoe from the south takes you over the wild and remote Rannoch Moor. Here the ghosts of the ancient past roam in the mist, telling tales of outlaws and fugitives, kelpies and lost swords. Black stumps of ancient trees still rest in the bog, and huge rocks litter the moor, which according to legend were thrown there by giants.

Ever since my earliest childhood, the magic of Glencoe and the journey to it has been seared in my soul as a place that defines what Scotland means to me. I visit as often as I can, in all seasons.

About nine years ago, I was driving a tour bus along this very route. We were heading for Loch Ness, of course, but I always looked forward to the journey through Glencoe, and did my best to always stop for a moment to allow people to photograph The Three Sisters.

On this day, the weather was weaving magic. Snow and sleet were being whipped up into eddies on Rannoch Moor, which was a white blanket of mystery. Buachaille Etive Mor, the mountain which guards the entrance to Glencoe from the south, was a pinnacle of snow and frost.

I remember my senses tingling when I first saw The Three Sisters appearing through swirling mist. They had their winter clothes on, a stunning, sparkling white.

But, as ever, the weather was changing by the minute.

As we came down from the moor into the glen, dark angry clouds descended, bringing freezing rain and sometimes hail, then cleared again to give moments of crisp sunshine.

The timing was perfect. I arrived at The Three Sisters viewpoint just as it stopped raining and a low-lying sun streaked its yellow rays across the glen.

There was a frenzy of fumbling for cameras as people scrambled out of the bus to take photos. I watched as another dark cloud approached and knew I’d have no trouble getting people back onto the bus. Sure enough, 10 minutes later the cloud engulfed us with wet hail, creating a stampede back onto the warm vehicle.

But job done, great photos, and now off to our lunch stop at Fort William. I pulled out carefully from the lay-by and began to tell the story of the massacre of Glencoe. But then there was a crunching sound and the bus broke down.

We were around 70 metres away from the lay-by, taking up the whole lane on one of the busiest tourist roads in Scotland, in icy conditions. Just above us there was a curve in the road where traffic of all kinds pours downhill, with drivers often being distracted by the spectacular scenery.

The rules were clear. The passengers must get off the bus to a safe place, and warnings put on the road for other vehicles approaching. There were howls of protest from some that they wanted to stay on the bus, but most could easily see the danger we were now in. I had to insist.

And so around 40 passengers disembarked and I led them along a semi-frozen path back to the vantage point where they had been only minutes before. I managed to call for help and waited with my passengers, telling them the tale of the massacre as the weather once again closed in. It now had new meaning to them as they huddled together against the wind and hail.

Thankfully, a mechanic quickly arrived from the nearby village of Ballachulish. He examined the bus and identified what was wrong. He came over to me and said he could fix it but would need a small part from the garage. He got onto his mobile and phoned his colleague.

“Wow, is that Gaelic?” asked a passenger who overheard the call.

“No, it’s Polish,” I said.

I did ask the mechanic his name and I think it was Marek; apologies if my memory got this wrong. But what is for sure is he was originally from Poland and settled in Scotland, which he called home. Now he was rescuing an international group of frozen travellers under the shadow of The Three Sisters of Glencoe.

True to his word, he fixed the bus quickly once his colleague, also Polish, arrived with the part. Forty very thankful people re-boarded the warm bus and we set off for lunch. The whole drama had taken only 50 minutes, although it had felt much longer.

There are thousands of years of stories and memories seeped into the history of Glencoe. Every time I visit, I remember those 50 minutes of it. Marek is now part of the story of the glen.

Our land is the story of people coming and making it home, my parents included. It is also the story of people being migrants, leaving Scotland to seek a new place to call home because of oppression, homelessness and poverty. Our history doesn’t stop at a given moment like a film, it keeps rolling; with new characters, new definitions, new identities and new perspectives, and new additions.

In East Lothian, a group of women originally from Poland have made the county home and now have family here. They love it so much, the history and the landscape, they have made a series of ‘Play Maps’ to encourage families to explore the heritage on their own doorstep. It is as much their heritage now as anyone else’s and what a fantastic contribution to enjoying it they have made.

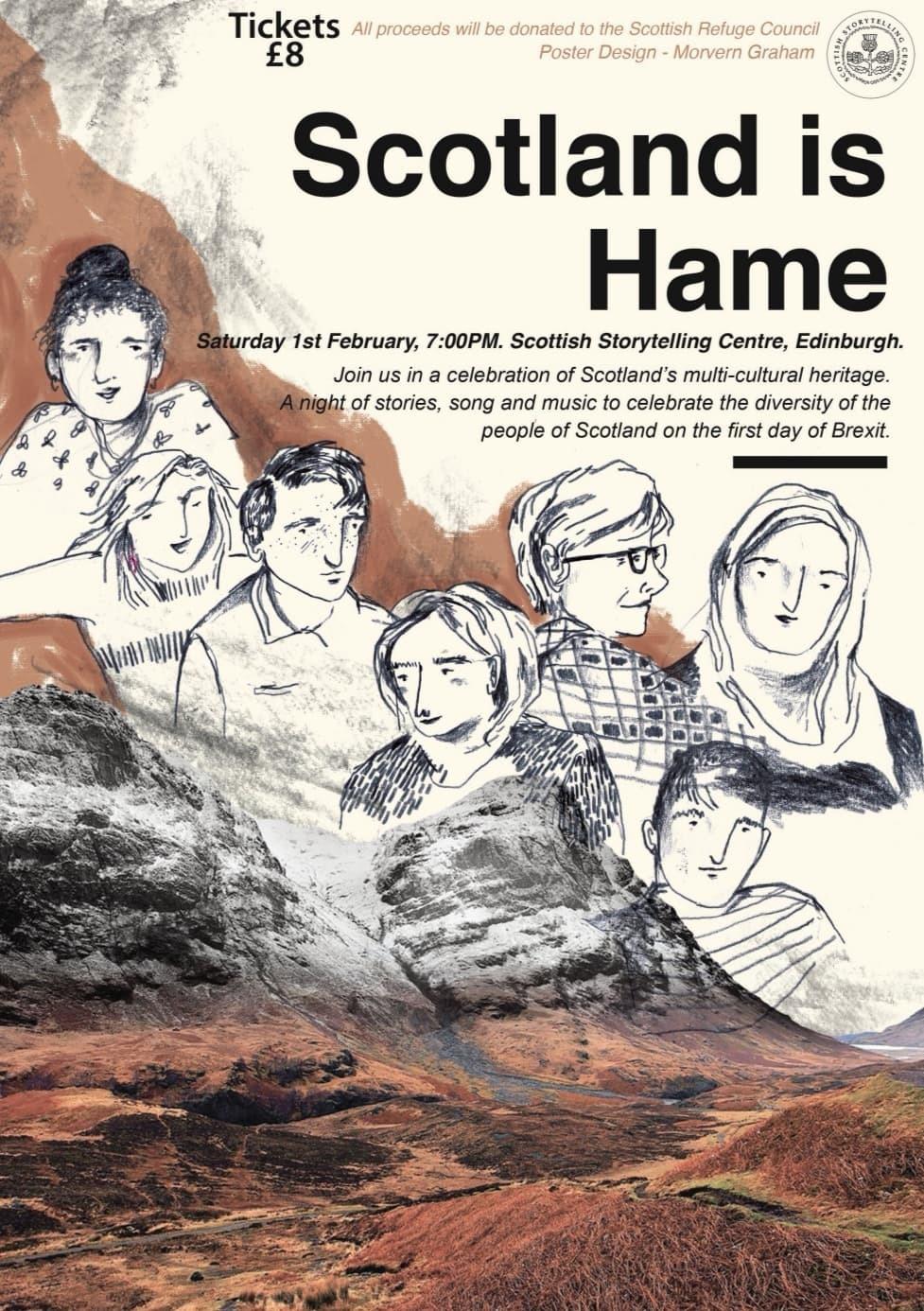

On Saturday, I will be joining them, along with storytellers who hail from different places including Denmark, Lithuania, Finland, Germany and Poland, at the Scottish Storytelling Centre in Edinburgh for an event called Scotland is Hame.

What will unite us will be the belief that Scotland is, and should be, a welcoming and inclusive home for us all, regardless of our origins, colour of our skin, faith or cultural background. I’m leaving a light on for that vision.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here