ON JULY 16, 1918, a newspaper had the following extraordinary story:

‘In the Amazing Confessions of Col. Otto von Heynitz, Principal Aide-de-Camp to the German Crown Prince in the Field, and now detained in Switzerland – (the book is edited by Wm. Le Queux) – appears the following line:

“Oh, how you British have been bluffed, my dear Le Queux! Before the War the Count – (Col. Count von Neumann Cosel, a friend of Col. Otto von Heynitz) – lived as a gentleman of independent means in your country, in a fine house near Dunbar in Scotland, and under an assumed name secretly directed the German Military Survey of your country.’”

The exasperated newspaper journalist asked himself: “Is this not deplorable and shocking? Wasn’t it a German officer who said ‘You British are always fools, and we Germans can never be gentlemen?’ Are we even now learning the bitter lesson of experience?”

But before we accept this highly charged account of the German spy ring in Dunbar, there is one name standing out – that of the writer and self-publicist William Tufnell Le Queux (1864-1927).

The son of a poor French immigrant, he received a rudimentary education before becoming a journalist writing for the cheap evening newspapers.

10 novels in a year

He married an Englishwoman who fell downstairs and died, and later an Italian woman who divorced him, took him to court and left him a bankrupt.

Le Queux published his first novel in 1891 and for many years his literary output would be very considerable, in quantity at least.

The prolific Le Queux could write 10 novels in a year, aside from numerous magazine articles.

Melodramatic adventure stories, old-fashioned even by the standards of their time, they featured a strong and manly hero, often a well-travelled clubman of independent means.

The villain was usually a foreigner, fond of inventing various cunning stratagems to put an end to his enemies, by using explosive bon-bons, a cobra in bed, tetanus in soup and rabies in ointment, or an electrified statue.

The heroine was young and naïve, and often under the influence of the villain.

The villainess was a ‘modern woman’, often French and intent on seducing the hero.

But in the end, the villain was confronted, some punishing right hooks administered, and the heroine saved from her peril.

A xenophobe to the core

These silly and repetitive books sold reasonably well, and the admirers of Le Queux were said to have included Queen Alexandra, A.J. Balfour and the young Graham Greene.

William Le Queux was a xenophobe to the core and, not entirely unreasonably, as events would turn out, he warned about Britain’s lack of military preparedness and declared that war was imminent.

In 1906, he published The Invasion of 1910, an alarmist account of how the Germans crossed the Channel and waged battle, committing various atrocities and besieging London and other major cities.

Supported and serialised by the Daily Mail, it became a huge bestseller and Le Queux was safe from the bankruptcy court, for some years at least.

He developed an obsession with German spies preparing for the invasion, publishing Spies of the Kaiser and other alarmist works.

When patriotic people wrote to Le Queux describing suspected spies they had seen, he forwarded their letters to the military.

He also developed an obsession that German agents were out to ‘neutralise’ him but, when he wrote to the police, they declared that he was a jittery person with a vivid imagination, who was not to be taken seriously.

Unmasking the Ripper

In a book of memoirs written by Rasputin – which no one else had ever seen – Le Queux claimed to have found out the identity of Jack the Ripper: it was an insane Russian surgeon named Alexander Pedachenko, who had gone over to London during the Autumn of Terror for some perverted ‘fun’.

Serious Ripperologists have objected that Pedachenko did not exist and that Rasputin never wrote a manuscript about great Russian criminals.

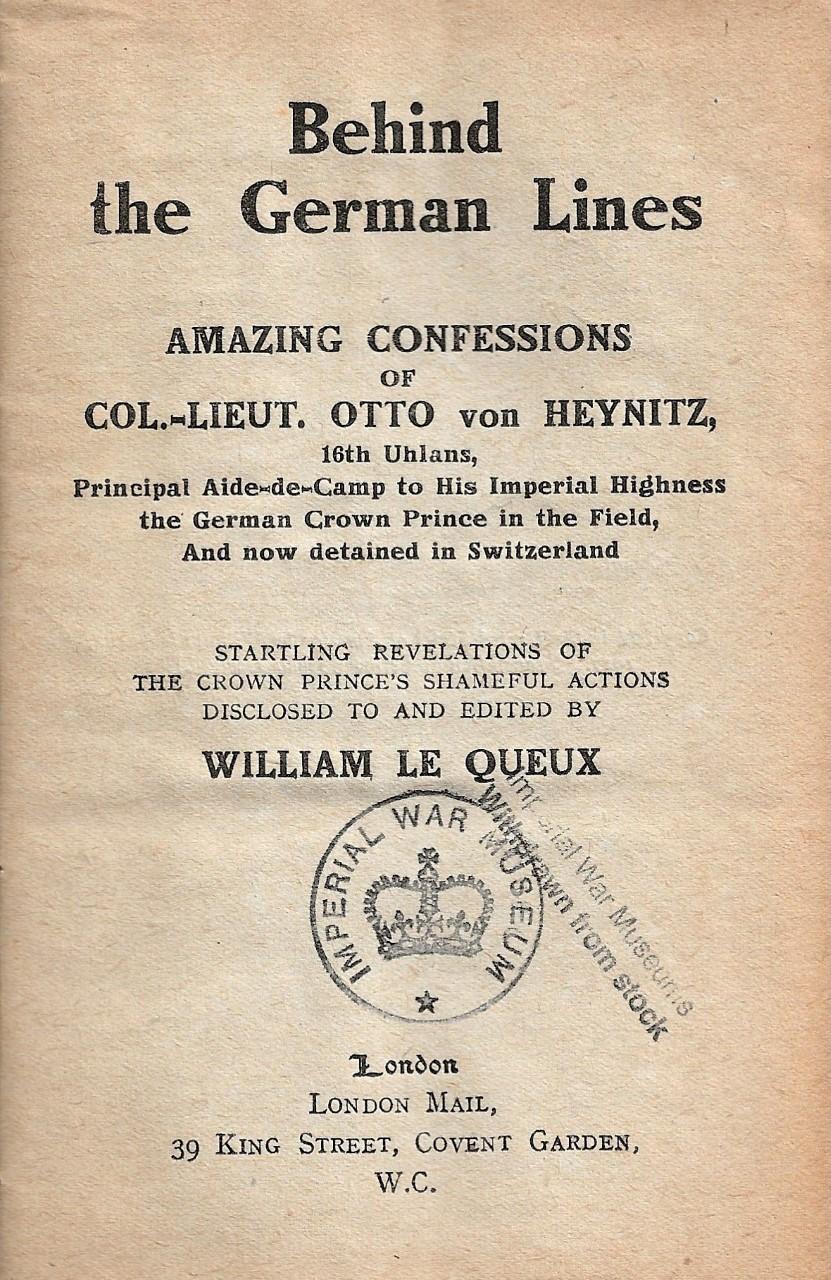

Two of the 15 books William Le Queux published in 1917 were Hushed up at German Headquarters and Behind the German Lines, consisting of the amazing confessions of Col.Lieut. Otto von Heynitz.

This Prussian cavalry officer of the 16th Uhlans, who had seen much active service in the Great War, had at length become disillusioned with the German wartime atrocities and taken refuge in Switzerland.

Le Queux claimed to have visited him there, to be entertained with a large quantity of spicy gossip from Otto the Blabbermouth: that the Crown Prince of Germany was constantly pursuing women all over Germany, seducing some of them when their husbands were at the front, and the Kaiser’s other sons were also leading immoral lives.

The front page of the first volume of the bogus memoirs of Otto von Heynitz, ex libris the Imperial War Museum

Otto von Heynitz was himself constantly in pursuit of attractive foreign women he encountered in the service of the Crown Prince, although his attempts to emulate his lecherous royal master repeatedly came to naught; in an (unintentionally?) comical episode, Otto was slipped a spiked drink by a beautiful American female spy and knocked out cold!

Otto von Heynitz also had much to say about the German spies and saboteurs who had been infesting Britain in the pre-war years, including the sensational details of the Dunbar spy ring.

Too good to be true

My own reaction was the story was too good to be true, however.

How could an entire troop of German spies operate from a fine house near Dunbar, without drawing attention to their activities, at a time when the members of the Teutonic tribe were viewed with great suspicion in Britain?

Inquiries via the Ancestry website revealed that although ‘von Heynitz’ and ‘von Neumann Cosel’ are bona fide German names, no member of these two noble families with the right name was in a position to have served in the Great War.

The British Newspaper Archive indicated that The Berwickshire News had been alerted to the story of the Dunbar spy ring after Behind the German Lines was featured in The Sunday Post and serialised in The Weekly News.

What seems to clinch this matter is a series of articles in the Critical Survey magazine of 2020, clearly demonstrating that William Le Queux was a systematic liar, who invented war propagandist stories and deliberately spread disinformation.

There is no doubt in my mind that Otto von Heynitz was nothing more than a figment of Le Queux’s fertile imagination, and that his ‘confessions’ were works of fiction rather than fact.

After all, the Crown Prince of Germany was a respectable person who took his military duties seriously and had no time to chase women all over Europe.

Thus the story of the sinister Dunbar spy ring is nothing but an unsavoury piece of wartime propaganda, spread by a literary hack who regurgitated fiction for fact during the wartime years, before receiving a well-deserved post-mortem come-uppance from modern internet detectives.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here