Dunbar author Dr Jan Bondeson continues his colourful exploration of the county’s rich past with a delve into the history of Whitekirk

ABOUT the 12th century, the ancient church of Whitekirk became famous due to its holy well, dedicated to St Mary the Virgin, which attracted pilgrims from far away.

Whitekirk was on the route of the pilgrims travelling from St Andrews to Santiago de Compostela, and they all used to stop here for prayer and a meal or two.

In 1356, King Edward III of England plundered the church, desecrated the shrine of Our Lady at Whitekirk, and took away the thanks offerings left by the pilgrims.

In contrast, King James I of Scotland placed the church under his personal protection, also having hostels built nearby to shelter the growing number of pilgrims.

In 1435, Aeneas Silvius Piccolomini, later to become Pope Pius II, was travelling to Scotland on a diplomatic mission as a Papal legate when his ship was beset by a severe storm.

After the crew said a solemn prayer to Our Lady, the ship made it safely to Dunbar.

Piccolomini had promised to walk barefoot to the nearest shrine to the Virgin; he is said to have made it all the way to Whitekirk.

During the siege of Tantallon in 1651, Oliver Cromwell used Whitekirk to billet his soldiers, who stabled their horses in there.

In Georgian and Victorian times, peace returned to Whitekirk, which with time had become a small village with a street lined by traditional East Lothian cottages.

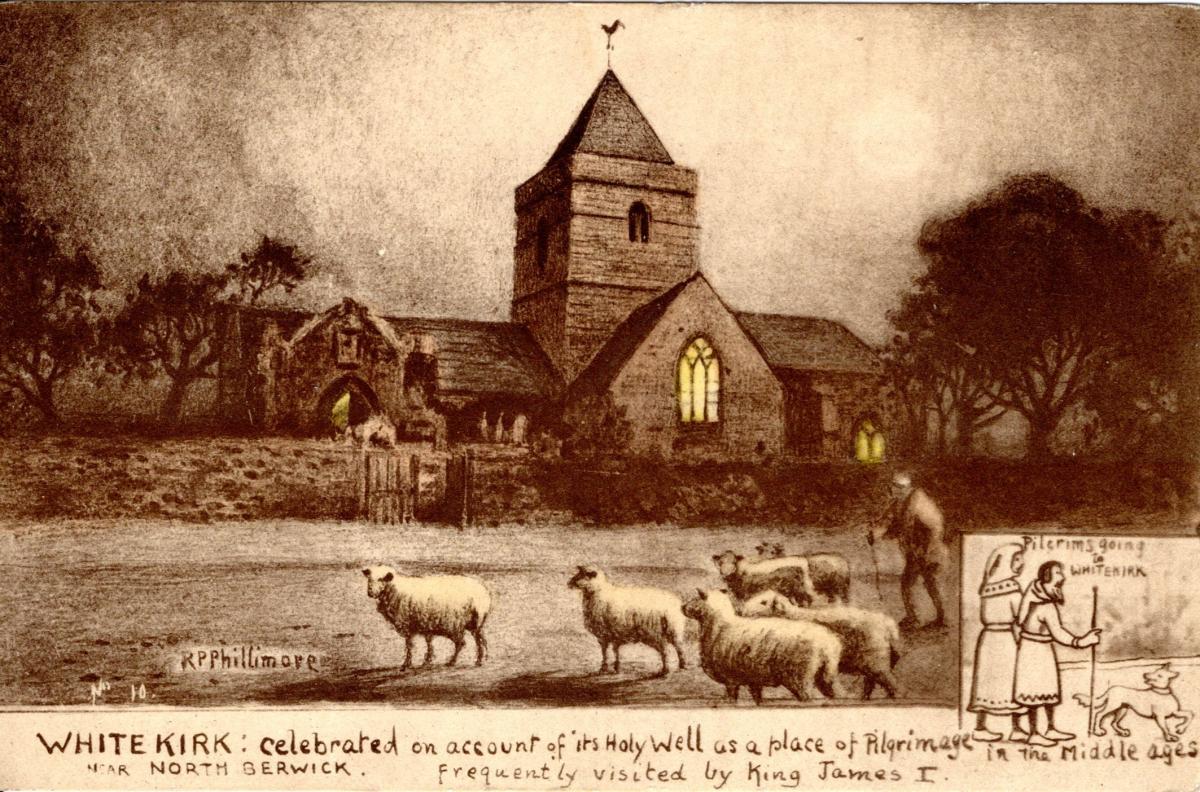

The village and church were a peaceful and bucolic sight when depicted by the celebrated North Berwick postcard artist Reginald Phillimore in Edwardian times, although the holy well had by now disappeared due to agricultural drainage.

Whitekirk before 1914

But this would all change in early 1914!

At shortly after 4am on Thursday, February 26, 1914, Mrs Rutherford, wife of the Whitekirk beadle, was awakened by a loud crackling noise.

Looking out, she was horrified to see that the old church was ablaze.

The beadle, in scant attire, hurried to the scene, hoping to save an invaluable old Bible inside the church, but he was driven back by the scorching flames and smoke.

He could only just see some suffragette leaflets scattered at the rear of the church, with messages such as “By torturing some of the finest and noblest women in the country you are driving more women into rebellion!”, “No surrender! Coercion the councel of fools and the spur to rebellion!” and “Stop forcible feeding of pioneers of freedom under the Cat and Mouse Act!”

Beadle Rutherford could not extinguish the fire or rescue the ancient Bible; he had to stand back as the valuable stained glass windows were blown out, the fire burning until only the bare walls were still standing.

Detective Sergeant Rae, from the Haddington police station, arrived on his motor bicycle at 6am and did his best to secure the evidence available.

The arsonists had entered through a window after smashing it with an American claw hammer, which was retrieved from the churchyard along with a formidable knife with a corkscrew and some more suffragist propaganda material.

A mysterious motor car had been parked in the village, and since its number had been taken this was considered a vital clue.

According to The Times of London, a red car in which several women were seated had passed through North Berwick travelling west, but none of the Scottish newspapers mentioned this vehicle.

Detective Sergeant Rae declared himself certain that the fire had been started by suffragettes. He presumed that they had doused the contents of the church with flammable liquids, before setting off two powerful incendiary devices.

There was much newspaper indignation that historic Whitekirk had been set on fire, The Scotsman writing: “Two bombs explode! By an outrage of the most dastardly nature, obviously the work of suffragettes: one of the historic churches of Scotland, the Parish Church of Whitekirk, in East Lothian, a splendid relic of the pre-Reformation days, has been completely gutted by fire, and many valuable articles have been destroyed.”

Mourning his destroyed church, the Rev Edward Rankine, the local parson, wrote that: “Some women did a fiend’s work here on Thursday morning.”

All the clues gathered by Detective Sergeant Rae turned out to be worthless: the vehicles observed nearby had innocent reasons to be in Whitekirk, and none of the locals had any arsonist tendencies or a grudge against religious buildings.

In June 1914, suffragette Janie Allan wrote to the chairman of the Prison Commission that Whitekirk had been attacked as a retaliation for the suffragette Ethel Moorhead having been force-fed at Calton Prison.

If two other suffragettes suffered the same indignity in Perth, the imminent royal visit to Scotland would be disrupted in a memorable and disastrous manner, she threatened.

A clue to the perpetrator of the Whitekirk attack can be obtained from the Allan memorandum – the church was set on fire just hours after Ethel Moorhead had been released from prison for window-breaking and attempted arson.

Her best friend was another suffragette named Frances Mary (Fanny to her friends) Parker, the niece of Lord Kitchener and a schoolmistress by trade, who had been a militant member of the Scottish women’s suffrage movement since 1908.

These two suffragettes had a record of vandalism and fireraising, horse-whipping people who had annoyed them, and throwing cayenne pepper into the faces of police constables and other figures of authority.

Fanny was strongly suspected of having burnt down the stand at Ayr Racecourse and the Perth County Cricket pavilion.

She was a tough and courageous woman, still just 39 years old in 1914, and perfectly capable of setting fire to Whitekirk, having stockpiled incendiary bombs and staked out the old church in advance.

Ethel is unlikely to have accompanied her, since she was suffering pneumonia caused by a mishap with the force-feeding, and was under the care of an Edinburgh lady doctor; but there were plenty of junior recruits ready to strike a blow for women’s suffrage.

On the morning of July 8, 1914, two women rode their bicycles up to the birthplace of Robert Burns in Alloway, South Ayrshire.

Seeing them tinker with something near the wall of this hallowed old cottage, a suspicious watchman came up to investigate what they were up to.

One of the women was arrested but the other escaped; when the watchman saw that they had been trying to light a fuse leading to two large bombs, he realised that he was dealing with suffragettes.

The birthplace of Robert Burns, which was narrowly saved from being destroyed by suffragettes

At Ayr Sheriff Court, the captured woman gave her name as Janet Arthur.

In the dock, ‘Janet’ quoted Burns’s patriotic song Scots Wha Hae, exclaiming that the Scots had once been proud of their national poet, but had taken to torturing women instead!

In jail, the suffragette promptly went on a hunger and thirst strike and had to be removed to Perth Prison and forcibly fed.

A certain Captain Parker came up from London, since he was worried that his sister was being mistreated; he told the Scottish authorities he had no sympathy with her views, but that she came from a distinguished family, being the niece of Lord Kitchener.

This let the cat out of the bag, and the Scottish newspapers published the true identity of the imprisoned woman.

Fanny Parker was eventually removed to a nursing home, from which she promptly escaped. Although definitive proof of her guilt is lacking, she remains the prime suspect for the Whitekirk attack.

At the outbreak of the Great War, there was an amnesty for the suffragettes, Fanny Parker included. She joined the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps in an administrative capacity. She took her duties seriously and did well, being twice mentioned in dispatches and awarded a military OBE.

After the war, she stayed well clear of Whitekirk in particular and East Lothian in general, instead moving in with Ethel Moorhead, who had since admitted being the second woman behind the attempt to destroy Burns’ cottage in Arcachon near Bordeaux.

Fanny died on January 19, 1924, leaving much of her property, valued at more than £5,000, to Ethel.

Whitekirk was rebuilt and restored under the direction of Sir Robert Lorimer; it was a pleasant and rural sight when I came to visit in 2019 for my book Phillimore’s East Lothian, and still stands today, in good order.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here